What a CIO does becomes clear when viewed through the organizational need that established the role. Every organization depends on a system that determines how information is structured, how technology is governed, and how digital capability supports performance. The Chief Information Officer formalizes this system. The role reflects an organizational requirement, not a technological trend: enterprises need a defined mechanism for directing how digital resources are designed, controlled, and scaled.

This requirement emerges from the complexity of modern operations. As processes, decisions, and interactions rely on interconnected digital systems, the enterprise must designate a single executive accountable for the logic that governs those systems. The CIO fulfills this mandate by establishing the principles and governance models that determine how technology shapes the organization’s capacity to function, adapt, and compete.

The CIO role is therefore best understood as the structural position that embeds digital capability within the enterprise architecture. The responsibilities associated with the position derive from this institutional purpose rather than from the mechanics of technology itself.

What Does a CIO Do?

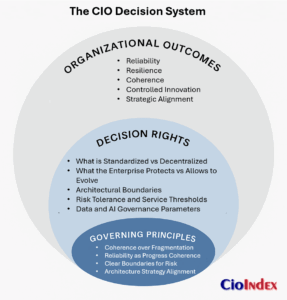

A CIO directs how an organization’s technology, information, and digital operations function as a coordinated system. The role translates enterprise objectives into decisions about technology investment, operational standards, security controls, data architecture, and digital capability. What a CIO does, in practice, is determine the governing rules under which these domains operate so the organization can perform reliably, manage risk effectively, and evolve its digital capacity with intention.

This work spans several interconnected areas. The CIO sets the principles that guide technology strategy, defines the conditions under which IT services operate, establishes the boundaries of acceptable digital risk, shapes how data is structured and governed, and directs the modernization efforts that reconfigure business processes. These actions form a unified decision system rather than a collection of tasks, and they anchor the CIO’s authority within the enterprise.

The CIO’s responsibilities are therefore not limited to technical oversight. They encompass the design, governance, and continual adjustment of the digital environment that supports the organization’s performance. This decision system provides the foundation for the specific domains of accountability explored in the sections that follow.

What Is a CIO? — Role Definition and Distinction

A Chief Information Officer is the executive who holds institutional authority over how digital capability is organized and governed within the enterprise. The role defines the structural model through which technology decisions are made, how responsibility for digital systems is distributed, and how information resources are managed at scale. A CIO provides the interpretive framework that connects technology to organizational performance, ensuring that digital capability functions as an integrated part of the enterprise architecture rather than as a set of isolated tools.

The structural mandate of the CIO distinguishes the role from adjacent technology leadership positions. The CTO concentrates on engineering and platform construction. The CDO directs the stewardship, lifecycle, and meaning of data. The CAIO governs the standards, controls, and ethical boundaries of artificial intelligence. Each role addresses a specific dimension of digital capability. The CIO’s remit is broader: it coordinates the governance logic that links these dimensions and ensures their collective alignment with enterprise direction.

The CIO vs Adjacent Technology Leadership Roles

| Role | Primary Mandate | Core Decision Focus | Enterprise-Level Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIO | Govern how digital capability is organized, aligned, and sustained across the enterprise. | Architecture, technology portfolio, digital risk posture, data/AI governance boundaries, modernization trajectory, and technology operating model. | Overall coherence of the digital environment; ability to execute strategy reliably and adapt with discipline. |

| CTO | Design, build, and evolve the technology platforms and engineering capabilities. | Engineering standards, technical stack choices, performance, scalability, and integration of platforms and services. | Technical robustness, delivery velocity, and the quality and extensibility of core systems. |

| CDO | Ensure data is accurate, meaningful, governed, and usable as a strategic asset. | Data models, data lifecycle, quality standards, access rules, and how information is interpreted and shared. | Reliability of information, analytic readiness, and the organization’s ability to reason from trusted data. |

| CAIO | Govern the use of AI and advanced models within defined ethical, regulatory, and operational boundaries. | Model selection and oversight, training data constraints, transparency requirements, usage policies, and AI-related risk controls. | Integrity and legitimacy of AI-driven decisions; ability to scale AI without undermining trust, compliance, or control. |

The CIO role is positioned at a point in the enterprise where strategic direction, operational realities, and information governance intersect. This positioning gives the CIO visibility into how technology choices influence organizational constraints and possibilities. It also places the role at the center of cross-functional coordination, where competing priorities must be reconciled into a coherent digital posture. This vantage point, rather than any specific technical expertise, defines the CIO’s strategic relevance within the leadership system.

The CIO’s Decision System — How the Role Actually Works

A CIO operates through a defined system of decision rights that determine how technology capability is shaped and governed across the enterprise. These decision rights do not prescribe specific actions; they establish the principles under which actions can occur. They define what the organization will standardize, what it will decentralize, what it will protect, and what it will allow to evolve. The CIO’s influence is expressed through the clarity and consistency of these governing choices.

This decision system spans several critical territories. It sets the criteria for technology investment and prioritization. It determines the operating conditions for digital services, the level of reliability the organization is willing to guarantee, and the safeguards placed around information and infrastructure. It defines how data is structured for use, how analytical capability is developed, and how emerging technologies are assessed for integration. These domains define the boundaries of the CIO’s strategic discretion.

What distinguishes the CIO’s decision system is not the volume of decisions involved, but the interdependence among them. A choice about architectural coherence affects operational stability; a choice about data structure influences analytical capacity; a choice about risk tolerance reshapes security architecture. The CIO ensures that these decisions reinforce one another rather than create structural tension. This interdependence explains why the CIO function cannot be fragmented across multiple roles without losing coherence.

The pillars that follow represent the major domains in which this decision system operates. Each pillar is a field of governing choices, not an inventory of tasks. Together, they show how the CIO translates enterprise intent into the digital conditions that support organizational performance.

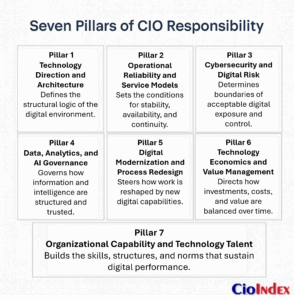

The Seven Pillars of CIO Responsibility

The CIO’s decision system operates across several domains that together define how digital capability is governed and sustained. These domains represent the structural areas in which the CIO’s authority shapes the organization’s technology posture, operational stability, security boundaries, information architecture, modernization pathways, economic model, and technical talent base. Each pillar reflects a field of governing choices that determine how the enterprise’s digital environment evolves and how it supports organizational performance.

Pillar I — Technology Direction and Architecture

A CIO determines the principles that guide how technology capability evolves.

This responsibility is not about selecting tools but about defining the architectural logic that constrains and enables the enterprise. The CIO decides which capabilities must be standardized, which can be modular, which require long-term stability, and which can accommodate experimentation. These architectural decisions establish the conditions under which the organization can scale, integrate new digital capabilities, and maintain coherence across its operating model.

Within this domain, the CIO sets the criteria for evaluating technology investments and the thresholds for adopting new platforms. These choices shape the organization’s technology trajectory by determining what will be supported, what will be retired, and how new capabilities will enter the environment without introducing structural fragility. Architecture becomes the mechanism by which strategy is translated into the configuration of systems and services.

This pillar defines the long-term digital shape the CIO steers for the enterprise.

Pillar II — Operational Reliability and Service Models

A CIO defines the operating conditions under which the organization’s digital systems must perform.

This responsibility centers on establishing the reliability thresholds, service expectations, and continuity requirements that determine how technology supports daily operations. The CIO sets the standards that govern availability, resilience, incident response, and service quality—standards that shape both the design of technology environments and the behaviors of the teams that manage them.

Operational reliability functions as a governance stance rather than a technical result. Decisions about redundancy, monitoring, capacity planning, and service models express the organization’s tolerance for disruption and the level of predictability it demands from its digital systems. These decisions influence vendor selection, architectural patterns, resource allocation, and the mechanisms through which operational performance is measured and escalated.

When service models are clearly defined and rigorously upheld, the enterprise gains a stable environment in which strategic and operational initiatives can proceed without friction.

Pillar III — Cybersecurity and Digital Risk

A CIO establishes the organization’s posture toward digital risk.

This responsibility defines the principles and constraints that govern how the enterprise protects its information, systems, and digital interactions. The CIO determines the boundaries of acceptable exposure, the mechanisms through which risks are identified and escalated, and the standards that shape the organization’s defense and resilience practices.

Cybersecurity decisions extend beyond threat mitigation. They specify how responsibilities are distributed across teams, how controls are embedded into technology workflows, and how the organization interprets regulatory and ethical obligations. These decisions influence architecture, vendor selection, data handling, and operational behaviors. The CIO sets the logic that determines when risks must be avoided, when they can be mitigated, and when they can be accepted as conditions of operating in a digital environment.

A defined risk posture strengthens trust, clarifies accountability, and enables new capabilities without introducing unmanaged exposure.

Pillar IV — Data, Analytics, and AI Governance

A CIO governs the principles that define the structure, interpretation, and controls to drive reliable data

These decisions establish the rules that determine what information the enterprise can trust, how that information acquires meaning, and how it flows across systems and functions. Data governance, in this sense, becomes a mechanism for shaping the organization’s interpretive capacity and ensuring that digital processes rely on information that is consistent and comprehensible.

Analytical work depends on the standards set for how insights are produced and validated. Choices about modeling discipline, interpretive methods, and analytical integration influence the organization’s ability to reason coherently. These standards prevent analytical practices from diverging into incompatible approaches and maintain a unified basis for decision-making.

AI governance extends this decision space. Determining the acceptable use of training data, the oversight required for model performance, and the constraints placed on automated decisions defines the boundaries within which AI can operate responsibly. These boundaries influence both the level of trust the enterprise can place in AI systems and the scope of their deployment.

When data, analytics, and AI operate under a coherent governance framework, the organization gains an information environment that supports reliable decisions and controlled innovation. This coherence reflects a central aspect of the CIO’s work: establishing the governing logic that shapes how digital intelligence is created, validated, and applied.

Pillar V — Digital Modernization and Process Redesign

A CIO directs modernization efforts by identifying processes for redesign, automation, and integration, steering digital change to enhance efficiency and maintain organizational coherence.

Modernization alters the assumptions under which the organization’s digital environment operates. Determining which processes require redesign, which systems constrain performance, and where new capabilities should reshape work patterns defines the enterprise’s trajectory of digital evolution. Such decisions place the CIO at the point where digital change must be steered toward coherence rather than allowed to fragment the operating model.

Process redesign relies on a governing logic that connects technological potential with enterprise intent. Choices about where simplification is necessary, where automation is feasible, and where integration will remove structural friction determine how digital shifts influence the organization’s operating rhythm. This logic sequences modernization efforts in ways that prevent isolated initiatives from producing incompatible outcomes.

A disciplined approach to modernization strengthens organizational coherence. When redesign initiatives follow principles that hold across functions, technology-driven change reinforces performance rather than disrupts it. Coherence arises when modernization adheres to a governing logic that the CIO enforces across initiatives.

Pillar VI — Technology Economics and Value Management

A CIO shapes the economic model for technology by evaluating investments, managing costs, and prioritizing capabilities that deliver sustainable value and align with strategic outcomes.

Technology economics exposes the CIO to decisions about where digital investment creates advantage and where it generates excess complexity or cost. Judgments about which capabilities justify continued funding, which require restructuring, and which should be retired determine how the organization’s technology portfolio evolves. Such judgments shape the economic contour of the digital environment and influence the rate at which new capabilities can be introduced.

Value management depends on a clear view of what each technology contributes to performance. Evaluating systems through their impact on productivity, control, risk posture, or strategic differentiation prevents digital capability from expanding as a set of entitlements. This evaluative discipline allows investments to be redirected toward areas where technology can alter organizational outcomes rather than sustain legacy patterns.

Financial structure becomes part of the CIO’s decision space. Principles governing cost transparency, sourcing models, and consumption patterns define how technology spending scales and how internal demand is moderated. These principles determine not only how resources are allocated but also how digital initiatives remain aligned with long-term economic boundaries.

An economic model grounded in these decisions gives technology strategy measurable direction. When investment follows a coherent logic, digital capability grows on a sustainable path, value becomes legible across the enterprise, and initiatives accumulate as strategic assets rather than fragmented expenses.

Pillar VII — Organizational Capability and Technology Talent

A CIO builds and organizes technical talent by defining skills, structures, and cultural norms that enable the workforce to sustain digital performance, adapt to new technologies, and execute strategy effectively.

Decisions about how technical talent is developed, organized, and deployed determine the enterprise’s ability to sustain digital performance — decisions that sit squarely within the CIO’s mandate. These choices shape the skills the organization cultivates, the roles it prioritizes, and the competencies it reinforces as technology evolves.

Capability building requires a framework that links workforce design to the demands of the digital environment. Judgments about which skills must remain internal, which can be sourced through partners, and which require new forms of collaboration determine how adaptable the organization becomes. This framework influences how teams are structured, how responsibilities shift, and how expertise accumulates over time.

Cultural expectations and leadership norms function as integral components of this capability system. Expectations about learning velocity, architectural discipline, security awareness, and analytical rigor become embedded in how teams operate. These norms influence whether digital initiatives scale effectively or stall due to skill gaps, inconsistent practices, or fragmented ownership.

A coherent approach to talent and capability enables technology strategy to translate into sustained performance. When workforce decisions follow a unified logic, the organization gains the capacity to absorb new technologies, maintain operational reliability, and advance digital initiatives without creating dependence on individual expertise or ad-hoc practices.

How the Seven CIO Pillars Translate Into Organizational Outcomes

| Pillar | What the CIO Decides | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Standards, stability, modularity | Coherence + scalability |

| Operations | Service reliability, continuity | Predictability |

| Risk | Exposure boundaries | Trust + resilience |

| Data + AI | Structure, meaning, model oversight | Interpretive accuracy |

| Modernization | Process redesign | Efficiency + integration |

| Economics | Investment logic | Sustainable value |

| Talent | Capabilities + norms | Long-term adaptability |

How CIOs Shape Enterprise Leadership and Governance

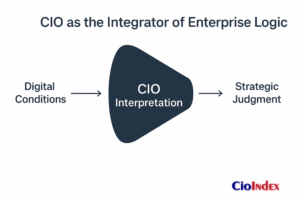

Leadership teams rely on a clear understanding of how technology shapes strategic options, operating constraints, and forms of organizational risk. The CIO contributes to this understanding by interpreting how the digital environment conditions the choices available to the enterprise. This interpretive role gives the CIO influence that extends beyond technology and into the core of strategic judgment.

Strategic deliberations sharpen when the CIO clarifies the structural implications of investment, risk posture, and capability development. Decisions that appear straightforward in isolation often carry long-term architectural or operational consequences. By making these consequences explicit, the CIO sharpens the leadership team’s ability to evaluate alternatives with greater precision and to recognize when short-term gains threaten long-term coherence.

Cross-functional coordination improves when the CIO clarifies the interdependencies that link technology decisions to financial, operational, and regulatory outcomes. Many of these interdependencies remain unrecognized until surfaced by someone with visibility across the full digital environment. Once articulated, they reshape how executives sequence initiatives, negotiate trade-offs, and maintain alignment across organizational boundaries.

Board oversight depends on an accurate view of the enterprise’s digital posture, and the CIO provides the analytical grounding for that view. Assessments of resilience, data integrity, security exposure, architectural commitments, and emerging technology possibilities require a leader who can translate system-level realities into governance-relevant insight. This translation enables the board to evaluate digital risk and digital opportunity with disciplined clarity.

The CIO becomes a stabilizing element within the leadership system by providing a consistent intellectual frame for decisions that involve technology, information, and organizational design. This frame links strategy, capability, and risk in ways that allow other leaders to make informed choices without needing direct expertise in the underlying systems. The result is a governance environment where digital complexity becomes interpretable rather than disruptive.

Leadership Implications of the Modern CIO Role

Technology has become inseparable from how organizations interpret complexity, allocate resources, and design their operating models. The CIO introduces a form of leadership grounded in the ability to translate digital conditions into strategic judgment. This translation requires a mode of reasoning that differs from other executive roles: the CIO assesses not only what is possible, but what remains viable when technology, risk, architecture, and capability interact.

Leadership at this level requires a high tolerance for interdependence. Decisions made in one domain alter constraints in others, and the CIO is often the only executive positioned to see these interactions before they surface as operational tension. This vantage point requires an ability to reconcile competing priorities with a coherent set of principles that hold across initiatives, preventing fragmentation in both strategy and execution.

Prioritization becomes a form of leadership discipline. The CIO must determine which digital capabilities advance enterprise goals, which create hidden liabilities, and which consume attention without contributing to long-term advantage. These judgments shape how the organization sequences change and where leadership attention is directed. The capacity to make these distinctions elevates the CIO from functional oversight to strategic stewardship.

The role also redefines accountability. Technology decisions carry structural consequences that extend beyond the teams directly responsible for implementing them. The CIO must articulate these consequences in ways that allow other leaders to assume shared responsibility for outcomes. This form of accountability shifts leadership conversations from isolated initiatives to system-level implications, strengthening collective decision-making.

CIO Leadership Logic vs. Traditional Executive Logic

| Executive Domain | Traditional Focus | CIO-Specific Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Market choice, competitive position | System viability and long-term digital constraints |

| Operations | Efficiency, throughput | Stability, interdependence, and architectural coherence |

| Finance | Cost control, budgeting cycles | Economic architecture, investment logic, and lifecycle value |

| Risk | Compliance and mitigation | Digital exposure, resilience, and systemic vulnerability |

| Talent | Skills and staffing | Adaptive expertise, capability systems, and digital workforce design |

A leadership model grounded in these capabilities influences organizational culture. Expectations regarding clarity, architectural discipline, resilience, and analytical rigor take shape around the CIO’s governing logic. When this logic is stable and well communicated, teams operate with sharper judgment, fewer unexamined assumptions, and a clearer sense of why certain choices prevail over others.

The modern CIO role recasts technology leadership as a structural force within the executive system. It positions the CIO not as a sponsor of digital initiatives, but as an architect of the conditions under which informed, coordinated, and future-oriented decisions can occur.

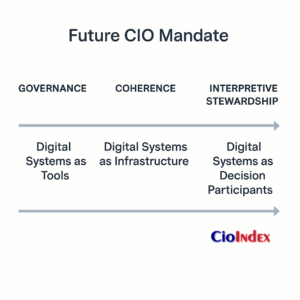

Forward Implications — What the CIO Will Need to Do Next

Digital systems are becoming participants in organizational decision-making, not just enablers of it. The CIO will need to govern the conditions under which these systems generate, evaluate, and influence judgments. This governance involves setting the principles that regulate how machine-derived insights integrate with human reasoning, how uncertainty is interpreted, and how automated outcomes gain legitimacy inside the enterprise.

Future architectures will amplify the strategic consequences of complexity. The CIO will need to prevent the accumulation of systems whose interactions exceed the organization’s capacity to control them. This requires a discipline that restricts architectural drift, clarifies the provenance of data and models, and enforces standards that maintain interpretive coherence across all digital capabilities. Without this discipline, technology becomes a source of opacity rather than intelligence.

Future situational awareness will be shaped by the informational and analytical structures the CIO establishes. Signal density will grow, patterns will shift more rapidly, and models will evolve faster than traditional governance processes can accommodate. The CIO will need to build decision environments that can absorb these dynamics without distorting strategic judgment or overwhelming operational stability.

Talent systems will require a different form of leadership. A workforce that operates alongside learning systems must possess the capacity to interrogate model behavior, recognize when assumptions fail, and adapt workflows to new patterns of automation. The CIO will need to define the competencies that enable this form of collaboration and design structures that support continuous recalibration of expertise.

Strategic coherence will depend on the CIO’s ability to impose intellectual discipline on digital evolution. The role will need to supply the conceptual structures through which other leaders interpret technological change, identify constraints, and recognize opportunity. Without these structures, the organization risks being shaped by technological momentum instead of deliberate strategic choice.

The CIO’s future mandate is to ensure that the enterprise’s intelligence infrastructure—its data, models, signals, and systems—operates with accuracy, alignment, and stability. As digital systems become more consequential in shaping how the organization understands itself and its environment, the CIO becomes the steward of the conditions that make informed action possible.

This trajectory brings the CIO role to a point where leadership depends not on technological proficiency but on the capacity to shape the conditions under which the enterprise interprets and acts.

A CIO who can shape the organization’s decision environment does more than guide its technology; they determine the clarity with which the enterprise understands itself.

Quick Reference of CIO Responsibilities:

- A CIO determines the architectural principles and standards that guide how technology capabilities are standardized, modularized, and evolved to ensure long-term coherence, scalability, and integration across the enterprise.

- A CIO establishes the reliability thresholds, service standards, and continuity requirements that define how digital systems deliver predictable, resilient performance to support uninterrupted business operations.

- A CIO sets the organization’s digital risk posture by defining acceptable exposure boundaries, control mechanisms, and escalation processes to protect information, systems, and interactions while enabling secure operations.

- A CIO governs the structure, interpretation, and controls for data, analytics, and AI to ensure trusted information, coherent insights, and responsible model deployment that support reliable decision-making and innovation.

- A CIO directs modernization efforts by identifying processes for redesign, automation, and integration, steering digital change to enhance efficiency and maintain organizational coherence.

- A CIO shapes the economic model for technology by evaluating investments, managing costs, and prioritizing capabilities that deliver sustainable value and align with strategic outcomes.

- A CIO builds and organizes technical talent by defining skills, structures, and cultural norms that enable the workforce to sustain digital performance, adapt to new technologies, and execute strategy effectively.