Introduction

Most IT governance efforts don’t fail in concept. They fail in translation.

Not because the principles are wrong or the frameworks are flawed—but because the journey from slide deck to system is harder than it looks. Governance plans are approved. Committees are named. Policies are published. And yet somehow, decisions still bypass the process, risks stay buried, and the architecture of accountability quietly collapses under the weight of business-as-usual.

The problem isn’t knowledge. It’s implementation.

This article is about closing that gap. Not through checklists or ceremony, but through structure that actually works—internally coherent, operationally grounded, and aligned with how the organization makes decisions in real life. Because governance isn’t just about who signs off. It’s about who gets heard. It’s about how priorities compete, how risk is surfaced, and how complexity is managed when everything is on fire.

And it doesn’t happen by accident. Real governance is built—strategically, deliberately, and with the long view in mind. It begins with planning: aligning intent with objectives, tailoring frameworks to fit culture, and designing operating models that can flex without breaking. Then it moves into execution: activating governance bodies, embedding process discipline, enabling visibility, and making sure the rules aren’t just published—but practiced.

This is the work of implementation. And it’s where the difference is made—not just between compliance and chaos, but between organizations that merely survive complexity and those that can steer through it.

If you’ve followed our earlier explorations—from defining what IT governance is, to how it works, to the frameworks that shape it, and the role it plays in managing risk—this article picks up the thread. It turns understanding into action. For a comprehensive perspective, these insights will ultimately form part of a broader resource designed to equip leaders with a full-spectrum view of modern IT governance.

Part I: Planning Your IT Governance Implementation

1. Assessing Organizational Readiness

Governance isn’t something you install—it’s something you integrate. And like any integration, success depends on fit. Before selecting a framework, launching committees, or drafting policies, organizations must understand the landscape they’re working with. Not just their technology architecture, but their decision architecture.

That means assessing readiness across three dimensions: capability, complexity, and commitment.

Capability is about maturity. Are governance structures already in place? Do roles, workflows, and escalation paths exist—even informally? Or is the organization starting from a blank slate? Maturity models like COBIT’s Performance Management framework or ISO/IEC 38500’s governance principles offer useful baselines, but they’re only valuable when grounded in reality. Many organizations overestimate their governance maturity because process exists on paper—even when it’s routinely bypassed in practice.

Complexity refers to the scope and scale of what governance must touch. A small IT shop managing centralized systems in one geography has different needs than a global enterprise navigating shadow IT, third-party vendors, overlapping jurisdictions, and federated business units. Complexity determines not just how many layers governance must traverse, but how adaptive it must be to remain effective.

Commitment is the most critical variable—and the least quantifiable. Governance implementation lives or dies on executive sponsorship. Without visible, ongoing support from the CIO, CFO, and business leadership, governance risks becoming a procedural layer without authority. Readiness isn’t just a function of structure; it’s a function of will.

Before proceeding, smart organizations conduct a reality check. Who makes IT decisions today, and how? Where do gaps exist between stated policies and lived behaviors? What cultural barriers stand in the way of change—and which leaders can champion that change? These questions don’t just inform the governance model — they determine whether it has any chance of working at all.

2. Defining Scope, Goals, and Governance Objectives

Governance is often derailed not by poor design, but by vague ambition. “We need better alignment.” “We want more control.” “We’re looking for discipline.” These are admirable instincts—but without sharper definition, they produce bloated governance models with unclear priorities and scattered impact.

The starting point is scope.

What exactly are you trying to govern? Strategy? Risk? Project portfolios? Architecture standards? Vendor relationships?

Governance can stretch across dozens of domains, but no organization can address them all at once. The key is focus: what must be governed first to unlock the value the business needs most?

Next comes alignment. Governance isn’t an end—it’s a means. And that means its objectives must trace directly to business outcomes. Want to reduce failed projects? Governance must touch demand management and resource allocation. Want to reduce risk? Governance must be wired into control points upstream of delivery. Want to drive innovation without chaos? Governance must define the guardrails that make safe experimentation possible.

Finally, define success. Governance that can’t be measured can’t be managed. This doesn’t mean chasing every KPI in the COBIT playbook—it means identifying 3–5 metrics that reflect the business value of governance: cycle time for IT decision-making, % of initiatives aligned to strategic priorities, frequency of compliance deviations, stakeholder satisfaction with IT investments.

Governance begins with intention—and intention needs clarity.

3. Selecting and Tailoring Frameworks

Frameworks are not plug-ins. They’re blueprints. And like any blueprint, they require customization before they can support the real-world load of a working enterprise.

There’s no shortage of models to choose from:

- COBIT for comprehensive IT governance across strategic and operational domains

- ISO/IEC 38500 for governance principles aligned to board-level oversight

- ITIL for service delivery governance

- PMI’s Organizational Governance Framework for portfolio governance in project-centric environments

Each offers structure—but none offer certainty. The right approach often involves a tailored combination: COBIT for overall governance, ITIL for process control, ISO 27001 for security governance, and internal models for strategic fit. The best implementations don’t follow frameworks religiously—they use them surgically.

Tailoring also means translation. Framework language doesn’t always resonate with business stakeholders. Terms like “value optimization” or “EDM processes” may work in the COBIT handbook, but lose impact outside IT. Implementation begins with building shared understanding. The framework must serve the organization’s culture—not the other way around.

And finally, remember this: adopting a framework doesn’t mean proving compliance to an external standard. It means using structure to make decisions better, faster, and safer. If a framework isn’t helping with that, it’s the wrong one—or it’s being used the wrong way.

4. Designing the Governance Operating Model

Governance without a model is just intent. Structure is what gives that intent traction. It defines not only where decisions get made, but how authority, accountability, and information flow across the enterprise.

The first decision is architectural: centralized, federated, or hybrid?

- Centralized governance consolidates authority within a single governing body—efficient, but often brittle when stretched across diverse business units.

- Federated models distribute governance, allowing business-aligned IT units more autonomy—flexible, but prone to fragmentation.

- Hybrid approaches attempt to balance both—central principles with local execution.

There’s no ideal. The right model reflects the organization’s size, complexity, risk appetite, and culture. A highly regulated financial services firm with a strong compliance culture may lean centralized. A multinational conglomerate with independent business lines may require a federated approach. Most fall somewhere in between.

Next comes the layering of governance functions:

- Strategic: C-level oversight, investment alignment, risk posture.

- Tactical: Portfolio gating, architecture reviews, vendor approvals.

- Operational: Day-to-day controls, change management, service levels.

Each layer needs clarity on decision rights. Who owns what decisions? Who provides input? Who signs off? Ambiguity here is fatal—it’s how projects get greenlit in one meeting and blocked in another. A well-designed operating model resolves these friction points with precision.

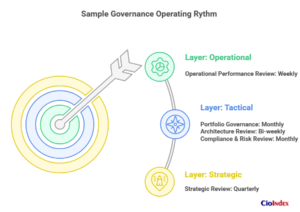

The graphic below shows how IT governance operates across three organizational layers, each with its own responsibilities and decision scope.

But design alone isn’t enough. Governance also requires rhythm. Decision forums must have a cadence. Governance reviews must have agendas. Reporting must follow cycles that match planning, funding, and delivery timelines. Otherwise, even the best-designed model will erode under the inertia of business-as-usual.

5. Defining Roles and Responsibilities

IT governance is, at its core, about who gets to decide what—and why. But clarity around decision rights doesn’t just happen. It must be built, communicated, and institutionalized.

Start with the major governance roles:

- CIO / CTO: Stewards of technology strategy, risk, and capability alignment with business needs.

- CFO / Finance Leads: Partners in value realization, cost optimization, and investment prioritization.

- Enterprise Architects: Custodians of standards, integration, and structural alignment.

- Business Unit Leaders: Co-owners of digital outcomes, jointly responsible for prioritization and benefit realization.

- IT Steering Committee (ITSC): The forum where cross-functional alignment is formalized and contested decisions get resolved.

- Architecture Review Board (ARB): A control mechanism to evaluate compliance with architectural and technical standards before significant IT investments move forward.

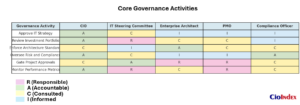

In practice, the distribution of responsibilities should be formalized through RACI matrices—mapping who is Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed for major governance activities. This becomes a living artifact, reviewed and adjusted as the organization evolves.

The chart below illustrates typical RACI role assignments across common IT governance decisions. Actual roles may vary based on organizational structure and maturity.

Governance roles aren’t static titles — they are behaviors. A CIO who rarely engages in project gating isn’t really accountable for portfolio governance. A steering committee that rubber-stamps everything isn’t governing. Real governance role clarity comes not just from organizational charts, but from observed patterns of decision-making and escalation.

6. Creating the Implementation Roadmap

No matter how compelling the vision, implementation fails when it tries to do everything at once. Governance must scale—not explode.

That begins with a phased roadmap, typically unfolding across three horizons:

- Phase 1: Foundations

- Establish governance bodies, define charters, introduce key policies.

- Pilot governance with a select portfolio or business unit.

- Identify early champions and quick wins.

- Phase 2: Integration

- Expand governance reach across business units and portfolios.

- Introduce supporting tools (e.g., dashboards, approval workflows).

- Formalize reporting cycles and escalation protocols.

- Phase 3: Optimization

- Integrate governance into enterprise planning and performance management.

- Refine policies based on real-world feedback.

- Extend governance to vendors, cloud partners, and emerging technology domains.

Each phase should be marked with clear milestones: not just “set up ITSC,” but “hold first three meetings with quorum and aligned decisions documented.” Not “create policies,” but “implement policy with compliance monitoring and feedback loop.”

Crucially, governance implementation must account for organizational change. New processes mean new behaviors—and that means friction. A strong roadmap includes stakeholder engagement, training plans, and resistance management. It treats governance not as a policy rollout, but as a cultural intervention.

7. Securing Sponsorship and Communicating the Vision

Governance cannot be imposed. It must be sponsored—visibly, vocally, and persistently.

Without senior leadership support, governance becomes another “IT thing.” It lacks legitimacy in business conversations, gets bypassed under pressure, and is abandoned when urgency trumps discipline.

CIOs and executive sponsors must position governance not as red tape, but as a business enabler:

- A way to reduce wasted investment

- A mechanism for risk transparency

- A platform for strategic alignment

- A shield against costly surprises

But even the strongest sponsorship fails without communication. Governance must be explained—not just what it is, but why it matters. Stakeholders at all levels need to understand how it affects their roles, decisions, and outcomes.

Effective governance communication isn’t a one-off memo. It’s a campaign—with messaging targeted to executives, project teams, finance, and operations. It uses real examples, avoids jargon, and anticipates skepticism.

And it’s sustained. Governance without narrative fades. But governance that tells a story—of accountability, value, and shared ownership—earns the political capital it needs to work.

Putting It into Practice: Two Organizations, Two Scales, One Discipline

While governance planning can seem abstract, its power becomes clear in context. Below are two contrasting examples that illustrate how the same core principles—assessment, scope, framework tailoring, operating model design, and structured rollout—can be adapted to vastly different organizational realities.

MetroLinea: Planning IT Governance in a Multinational Retail Enterprise

MetroLinea is a multinational retail organization operating across 15 countries with multiple digital touchpoints—e-commerce platforms, in-store systems, supplier networks, and a growing mobile customer base. Over the past three years, the company has pursued aggressive digital expansion but faced escalating issues: redundant applications, escalating cloud costs, regulatory non-compliance in EU markets, and multiple failed IT initiatives lacking executive oversight.

The CIO, in partnership with the CFO and Chief Risk Officer, initiated a structured IT governance implementation to address these challenges.

Phase 1: Readiness Assessment

- A maturity review using COBIT’s Performance Management tool revealed fragmented decision-making, with most strategic IT decisions made ad hoc by regional leadership without central visibility.

- Internal interviews highlighted strong executive willingness, but no shared language around governance.

- Complexity was identified as a key challenge: operations spanned multiple jurisdictions, each with different regulatory and operational demands.

Phase 2: Scoping and Strategic Objectives

- The initial scope was narrowed to three priorities:

- Portfolio governance: standardize project gating and prioritization across regions.

- Architecture governance: reduce tech duplication and enforce standards.

- Compliance oversight: ensure GDPR and payment security compliance in EU markets.

- Objectives were explicitly tied to measurable business outcomes:

- 15% reduction in IT operating costs through system rationalization.

- 100% project visibility by end-of-year across regional portfolios.

- Reduction of compliance audit findings to zero within 12 months.

Phase 3: Framework Selection and Tailoring

- MetroLinea selected COBIT as its primary governance framework, but applied it selectively:

- EDM processes for investment oversight and risk optimization.

- APO and MEA domains for performance tracking and policy enforcement.

- ITIL was integrated into service management functions already in use, while ISO/IEC 38500 was used to guide board-level engagement.

The organization avoided a wholesale rollout. Instead, each framework was mapped to existing processes to reduce disruption and cultural resistance.

Phase 4: Governance Operating Model Design

- A hybrid model was adopted:

- Central governance board for policy, strategy, and funding alignment.

- Regional governance units with autonomy to manage localized portfolios—within centrally defined thresholds.

- Three-layer model formalized:

- Strategic: CIO-led Enterprise Governance Board (EGB)

- Tactical: IT Steering Committees in each region

- Operational: Service management councils tied to shared services

Phase 5: Roles, Roadmap, and Communication

- A cross-functional RACI matrix clarified responsibilities across IT, finance, and compliance functions.

- The roadmap focused on three workstreams:

- Q1: Policy and charter development; establish EGB

- Q2: Launch project gating in EMEA and LATAM

- Q3: Implement architecture reviews and compliance dashboards

- A branded internal campaign—“Connected Decisions”—was launched to communicate the purpose and value of governance, supported by town halls and a governance microsite.

Outcome (Preview)

Though execution is still underway, early indicators show strong adoption. 90% of new projects now go through formal gating, and EMEA reduced its shadow IT application inventory by 23% in two quarters.

Why This Works

MetroLinea’s experience highlights key themes from Part I:

- Governance isn’t “one more thing”—it’s a discipline to coordinate everything.

- Strategic planning isn’t just templates and terms—it’s about understanding where governance fits, how it’s perceived, and what it’s solving for.

- Tailoring frameworks and operating models is essential—not to dilute governance, but to make it usable at scale.

ClearForge Ltd.: Governance in a Mid-Sized Manufacturing Company

Not every organization needs a steering committee, a layered governance model, or a fully customized COBIT implementation to make governance real. Sometimes, all it takes is clarity.

ClearForge Ltd. is a regional manufacturing company with just over 400 employees. Its IT function is lean—five people supporting ERP, infrastructure, and integrations with logistics and procurement vendors. For years, the CFO acted as de facto head of IT, approving budgets and greenlighting initiatives with little formal process. It worked—until it didn’t.

Projects started piling up. Vendor contracts were renewed without security reviews. A critical integration failed mid-quarter, costing the business a major client. In the aftermath, the leadership team didn’t demand more tools—they demanded more visibility. More discipline. And above all, more accountability.

What Governance Planning Looked Like

Readiness was quickly assessed: there were no governance bodies, no defined roles, and no escalation paths. But there was executive will, and that was enough to start.

Scope was narrowed to two essentials:

- Project intake and prioritization: to reduce the backlog and ensure alignment.

- Vendor oversight: to manage risk ahead of upcoming cyber insurance renewals.

Rather than adopt a full framework, the team used ISO/IEC 38500’s principles as a lightweight guide. Three simple rules were agreed:

- Every project must have a named business owner.

- All third-party vendors must be reviewed against a basic compliance checklist.

- Any IT spend over $5,000 requires joint approval from the CFO and Head of IT.

No new committees were formed. Governance was folded into existing monthly leadership meetings. A one-page RACI matrix clarified who initiates, approves, and monitors projects. Implementation was equally simple: a two-hour session introduced the new process, followed by a standing item on the operations report tracking active projects, pending decisions, and vendor risks.

Why It Worked

ClearForge didn’t overdesign. It didn’t aim for maturity models or certifications. It aimed for visibility, alignment, and shared responsibility—and it got them. Within two quarters, the IT backlog was reduced by 40%, vendor assessments were standardized, and for the first time, the executive team had a real-time view of IT commitments.

Table: Two Approaches to Governance Planning

| Element | MetroLinea (Global Enterprise) | ClearForge Ltd. (Mid-Sized Business) |

| Industry & Size | Retail, 15 countries, thousands of employees | Manufacturing, single-region, ~400 employees |

| Governance Maturity | Fragmented structures; regional decision autonomy | Informal, ad hoc IT oversight by CFO |

| Scope of Governance | Portfolio, architecture, compliance | Project intake, vendor oversight |

| Frameworks Used | COBIT, ITIL, ISO/IEC 38500 (tailored use) | ISO/IEC 38500 (light reference) |

| Operating Model | Hybrid model: central board + regional committees | Folded into existing leadership meetings |

| Artifacts Created | Charters, policies, dashboards, architecture review process | One-page RACI, intake form, reporting slide |

| Communication Strategy | Governance microsite, branded internal campaign | IT staff onboarding session, updated reporting template |

| Time to First Impact | 2–3 quarters | 1 quarter |

What These Cases Show

Governance planning isn’t about volume—it’s about fit. MetroLinea needed orchestration across borders; ClearForge needed alignment across roles. Both achieved traction by focusing governance on the decisions that mattered most, using structure to create clarity without creating drag.

The lesson is clear: governance scales—but only if you plan it to.

Part II: Operationalizing the IT Governance Framework

1. Establishing Governance Structures and Cadence

Planning defines purpose. Operationalization makes it visible.

The first step in bringing IT governance to life is to activate the structures designed during planning—committees, councils, boards, or integration points. This is where governance begins to surface in real meetings, real decisions, and real tensions.

But forming a committee isn’t the same as establishing governance. A steering committee with no quorum, no mandate, or no strategic link is theater. Governance bodies must be anchored in charters that define:

- Their purpose and scope

- Membership and quorum requirements

- Decision rights and escalation pathways

- Reporting responsibilities

Charters shouldn’t read like legal disclaimers — should be operational tools. Every meeting, every agenda, and every follow-up should reinforce the charter’s purpose.

Governance thrives on rhythm. The visual below shows how a mature IT governance function might structure recurring forums across layers—from strategic to operational.

Governance structures aren’t created in a vacuum—they’re often inspired by well-established frameworks like COBIT, ISO/IEC 38500, and ITIL. For a detailed breakdown of how these frameworks shape decision rights, escalation pathways, and governance mechanisms, see our article on: IT Governance Frameworks: An In-Depth Analysis of COBIT, ISO/IEC 38500, ITIL, and More.

Just as important is governance cadence. Strategic governance doesn’t happen on an ad hoc basis—it happens in rhythm:

- Portfolio decisions tied to quarterly planning

- Architecture reviews before key investment gates

- Monthly risk and compliance updates flowing into audit committees

Without cadence, even the best governance body becomes reactive or symbolic. With cadence, it becomes a predictable channel through which visibility, alignment, and control flow.

2. Embedding Governance in Core IT Processes

Governance isn’t just a structure — a thread. And it only works when woven into the operational fabric of IT.

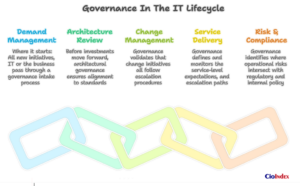

That means embedding governance into the critical decision and delivery processes:

- Demand Management: All new initiatives—whether technology-led or business-sponsored—must pass through intake gates that assess alignment, capacity, risk, and value.

- Architecture Governance: Major technology investments must be reviewed for adherence to enterprise standards, integration strategy, data policies, and security protocols.

- Change and Release Management: Governance ensures that proposed changes are reviewed not just for technical readiness, but for strategic relevance and risk exposure.

- Service Delivery: Governance aligns SLA definitions, incident escalation protocols, and vendor oversight with strategic outcomes.

- Risk and Compliance Management: Processes for risk identification, treatment plans, and control testing must be formalized and regularly reviewed.

Governance isn’t a checkpoint—it’s a connective thread. This diagram shows how effective governance embeds itself across the full spectrum of IT decision-making and delivery processes.

Too often, governance is layered on top of these processes as a compliance checkpoint. The goal is the opposite: governance should be the mechanism through which these processes are aligned, evaluated, and improved over time.

The test is simple: Can teams trace how governance decisions affect what gets built, how it’s built, and how it’s supported? If not, governance remains a PowerPoint, not a practice.

3. Deploying Governance Policies and Mechanisms

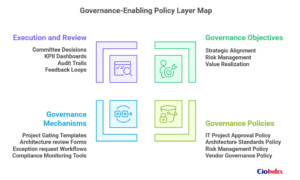

Policies are where governance becomes enforceable. But they must be more than declarations — they must be usable, visible, and actionable.

Start with a core set of governance-enabling policies:

- Project Approval and Gating Policy

- Architecture and Technology Standards

- Risk Management and Escalation Policy

- Vendor and Third-Party Governance Policy

- Data and Compliance Oversight Policy

Each policy should clarify what is expected, when it applies, who is responsible, and what happens in the case of exceptions. Importantly, there should be a mechanism to request, review, and approve exceptions—governance should enable flexibility where justified, not enforce rigidity for its own sake.

Alongside policies, deploy governance mechanisms—processes, workflows, and digital tools that make governance frictionless:

- Pre-configured templates for business cases, architecture review submissions, or project intake forms

- Integrated approval workflows that align with planning cycles

- Dashboards that make compliance visible and deviations actionable

Governance mechanisms should reduce ambiguity—not create it. Every time a decision-maker asks “Who approves this?” or “Where do I send this?” governance has failed silently.

Effective governance isn’t enforced by policy alone—it moves from clear objectives to enabling policies, into mechanisms that support decision-making, and finally into execution that can be tracked, reviewed, and improved.

4. Leveraging Technology and Tooling

Good governance cannot rely on memory, email, or institutional knowledge. As governance matures, it must be supported by systems—not to bureaucratize decisions, but to standardize access, visibility, and accountability.

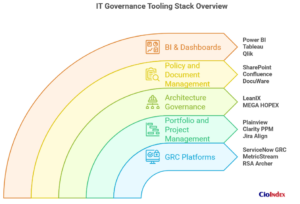

The tooling stack for IT governance typically includes:

- GRC Platforms (e.g., ServiceNow GRC, RSA Archer, MetricStream):

Automate risk management, policy compliance, control testing, and audit workflows. - Portfolio and Project Management Tools (e.g., Planview, Clarity PPM, Jira Align):

Provide visibility into initiative alignment, gating decisions, resource constraints, and benefits realization. - Architecture Governance Tools (e.g., LeanIX, MEGA HOPEX):

Support architectural reviews, technology lifecycle planning, and standards enforcement. - Policy and Document Management Systems:

Centralize governance documentation, version controls, and audit trails. - BI and Dashboard Platforms (e.g., Power BI, Tableau):

Make governance performance visible—project statuses, compliance exceptions, governance meeting KPIs.

The goal isn’t to overwhelm teams with tools—but to use technology as a multiplier:

- Streamline submissions and approvals

- Reduce email chains and undocumented exceptions

- Automate compliance tracking and reporting

- Surface patterns that manual reviews miss

Tools should also be integrated into the systems where decisions are made. If project approvals happen in Jira, then governance gates should live there—not in a disconnected spreadsheet. If executive dashboards are reviewed in Power BI, governance metrics must be surfaced there—not in a hidden PDF.

Governance is made real not only through structure and process, but through the tools that support consistency, visibility, and compliance. The diagram below maps the core tooling layers used to support enterprise-scale governance practices.

5. Building Capabilities and Governance Culture

Even the best-designed governance structures fail without people who understand them, believe in them, and use them well. That means building governance not only as a process—but as a capability and a culture.

Capability Building:

- Role-based training for everyone from committee members to project leads.

- Just-in-time education embedded in tools and workflows—tooltips, templates, checklists.

- Onboarding programs that include governance awareness for new IT staff, project managers, and business sponsors.

Culture Shaping:

- Frame governance as a value enabler, not a constraint.

- Highlight wins where governance prevented failure or enabled alignment.

- Recognize and reward good governance behavior—someone who flagged a misaligned initiative, escalated a risk early, or drove compliance improvement.

Governance is sustained not through enforcement, but through shared ownership. When governance is seen as everyone’s business, it stops being seen as someone else’s burden.

Governance culture is built step by step. The pyramid below illustrates the progression from basic awareness to full organizational ownership—each layer enabling and reinforcing the next.

6. Measuring, Monitoring, and Improving

What gets measured gets governed.

Governance must be auditable, visible, and improvable. That requires a performance framework with a small, powerful set of indicators:

Common Governance KPIs:

- % of IT initiatives reviewed and approved through formal governance gates

- % of projects aligned with strategic objectives

- of policy deviations and exceptions granted (trending up or down)

- Time-to-decision at major governance gates

- Risk identification and mitigation rates

- Stakeholder satisfaction with governance processes

Use these metrics not just to prove effectiveness, but to identify friction points. Where is governance slowing things down? Where are decisions bottlenecked? Where is compliance lip service rather than embedded practice?

Governance only works if it can be measured and improved. Below are examples of key performance indicators (KPIs) that reflect the health, maturity, and impact of IT governance efforts across different dimensions.

Embed metrics into dashboards used by both IT and business leaders. Governance must be part of leadership’s line of sight—not a back-office concern surfaced only during audits.

Finally, governance should include its own continuous improvement loop:

- Quarterly or biannual governance retrospectives

- Stakeholder surveys and governance maturity reviews

- Policy and charter refresh cycles

Governance isn’t static. It must evolve with strategy, risk, technology, and scale.

7. Sustaining Governance as a Living Capability

The most dangerous governance failure is not the one that never starts—but the one that fades after launch.

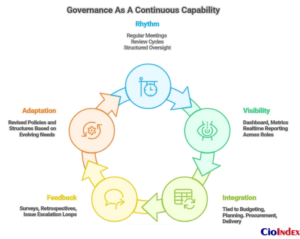

Governance must be sustained through:

- Rhythm: Regular meetings, review cycles, and reporting.

- Visibility: Dashboards, scorecards, and embedded performance indicators.

- Integration: Tied to planning, budgeting, procurement, and delivery—not adjacent to them.

- Adaptation: Revisited when mergers happen, org charts change, or new technologies emerge.

Organizations that treat governance as a one-time rollout find themselves back at square one within a year. Those that treat it as a living capability—designed to evolve, scale, and flex—make governance part of how the organization thinks, not just how it controls.

Governance that lasts doesn’t rest on structure alone—it flows through a continuous cycle of rhythm, feedback, and strategic adaptation. The visual below outlines how this capability matures and reinforces itself over time.

MetroLinea: Operationalization in Practice

In Part I, we explored how MetroLinea, a multinational retail enterprise, scoped and planned its IT governance implementation. With charters written, frameworks tailored, and an implementation roadmap in place, the real challenge began: making governance work in practice.

Activating Structures and Committees

MetroLinea launched its Enterprise Governance Board (EGB)—a strategic body composed of the CIO, CFO, Chief Risk Officer, and regional technology heads. The board met quarterly to review IT investments, prioritize initiatives, and oversee policy compliance.

To avoid governance fatigue, the company consolidated smaller decision forums into regional IT Steering Committees, each aligned to specific business units and meeting monthly. These committees were tasked with reviewing business cases, escalating cross-functional issues, and ensuring adherence to architecture standards.

Charters were not treated as formality. They were operationalized:

- Agendas were structured around the charter’s decision categories.

- Meeting outputs were documented in a centralized governance tracker.

- A quorum rule prevented symbolic participation and ensured accountability.

Embedding Governance in Core IT Processes

One of the most critical moves MetroLinea made was threading governance into existing workflows:

- All IT project proposals were required to pass through a newly developed Digital Initiative Intake Form, capturing strategic alignment, business value, risk exposure, and resource needs.

- Before any project above $250K proceeded, it underwent an Architecture Review. A cross-functional ARB evaluated technical feasibility, standards alignment, and integration readiness.

- Change Management was retooled: no production deployment could proceed without dual sign-off from the service manager and governance lead if the change exceeded predefined risk thresholds.

- Governance checkpoints were integrated into Jira for agile teams, ensuring policy compliance without disrupting sprint velocity.

By embedding governance into tools and delivery pipelines, it became an invisible but active layer—not a bottleneck, but a guidewire.

Policy Enablement and Mechanisms

MetroLinea rolled out five core governance policies in the first six months:

- IT Investment Approval Policy

- Architecture Standards and Technical Review Policy

- Vendor Risk and Performance Policy

- Data Governance and Compliance Oversight Policy

- Exception Handling and Escalation Policy

Each policy was supported by an operational mechanism:

- Pre-configured templates in SharePoint for submissions

- ServiceNow workflows for approvals

- Real-time dashboards in Power BI for policy adherence and exception tracking

These policies weren’t rolled out with fanfare—but with clarity. Each one was accompanied by:

- A walkthrough session with business and IT stakeholders

- Quick reference guides tailored by role

- Embedded links within existing tools

Building Culture and Governance Competency

Governance wasn’t treated as a separate initiative—it was embedded into performance expectations and leadership behaviors:

- Governance responsibilities were added to IT leadership KPIs.

- Training programs were tiered: foundational awareness for all staff, in-depth operational training for committee members and architecture leads.

- An internal recognition program spotlighted governance champions—project managers and architects who modeled good governance behavior.

Governance wasn’t just about process. It became language and mindset.

Performance, Feedback, and Iteration

MetroLinea defined a concise set of governance KPIs:

- % of projects gated through formal review (target: 90%+)

- of exception requests per quarter (trend tracking)

- Average cycle time from intake to decision

- Committee attendance and decision completion rates

A quarterly Governance Review Forum—separate from the EGB—was launched to:

- Analyze metrics

- Review pain points flagged by users

- Recommend policy or process adjustments

Within nine months, MetroLinea had:

- Unified its IT investment approval process across all business units

- Reduced ungoverned initiatives by 63%

- Achieved audit-ready compliance across three jurisdictions

Why It Worked

MetroLinea didn’t mistake governance for paperwork. It treated it as a capability—designed, implemented, measured, and adapted. By aligning governance with strategy, embedding it into process, and treating culture as a first-class requirement, the company transformed governance from overhead into strategic advantage.

The difference was not in what they governed—but in how they operationalized it.

ClearForge: Operationalizing Lean Governance

While MetroLinea’s governance rollout was multi-layered and global, ClearForge—a mid-sized manufacturer with a small IT team—focused on lean, integrated governance that didn’t require new roles or heavy frameworks. Its success wasn’t about complexity; it was about clarity, consistency, and ownership.

Minimal Structure, Maximum Focus

ClearForge didn’t establish a formal IT Steering Committee or new governance boards. Instead, it:

- Designated the monthly operations leadership meeting as the de facto governance forum.

- Assigned clear ownership: the CFO and IT Manager jointly reviewed all incoming IT projects over $5,000.

- Used a single-page charter to define the group’s governance responsibilities: project prioritization, vendor risk review, and policy exception escalation.

This worked because governance wasn’t seen as “extra”—it became a logical extension of operational decision-making.

Embedding Governance in Daily Operations

Rather than reengineering processes, ClearForge looked at where governance was already happening—informally—and made it explicit:

- All new IT project proposals were submitted using a basic intake form. It included purpose, cost estimate, business sponsor, timeline, and vendor.

- Vendor renewals and new contracts had to include a short risk checklist: data handling, system access, support availability, and certification.

- High-risk or high-cost projects required an email approval trail from both the CFO and the IT Manager before being greenlit.

There were no digital workflows or portfolio tools—just structured conversation and visible accountability.

Policy Without Bureaucracy

Instead of rolling out dozens of documents, ClearForge implemented just two lightweight policies:

- Project Approval and Intake Policy – defining who can propose, who approves, and how decisions are tracked.

- Vendor Management Policy – specifying what risk data must be reviewed and stored.

These policies were shared via a simple Confluence page and discussed during IT onboarding for any new team members. There were no checklists or portals—just clear expectations.

Building Buy-In and Capability

With only a handful of IT staff and business sponsors involved, capability-building was informal but effective:

- The CFO explained the purpose of governance during staff meetings.

- IT leads were encouraged to push back on unclear or underfunded requests—and rewarded when they did.

- A “Governance in Action” highlight was added to each month’s IT update slide—sharing how a decision was improved through the process.

Governance wasn’t about control. It was about shared discipline.

Results Without Complexity

ClearForge didn’t set KPIs in dashboards, but it did track outcomes informally:

- Fewer project restarts due to missing stakeholder input.

- Clearer vendor engagement terms—especially around support and data privacy.

- Fewer fire drills from last-minute IT purchases or unreviewed renewals.

Over time, leaders began using the phrase “Has this gone through governance?”—a sign that the habit had taken hold.

Why It Worked

ClearForge succeeded because it understood that governance doesn’t require an enterprise playbook. It requires:

- Visible ownership

- Simple tools that fit the context

- Consistency over formality

- And most of all, a willingness to treat decisions as investments—not tasks

Where MetroLinea operationalized governance at scale, ClearForge embedded it at the core of its everyday rhythm. In both cases, the implementation reflected the organization’s reality—and that’s why both worked.

Table: Comparing Governance Operationalization at Two Scales

| Element | MetroLinea (Global Enterprise) | ClearForge Ltd. (Mid-Sized Business) |

| Structures Activated | Enterprise Governance Board, regional Steering Committees | No new structures; monthly leadership meeting served governance role |

| Governance Integration | Formalized into Jira, ServiceNow, and project lifecycle gates | Integrated via intake forms and email approvals within existing ops |

| Policies Deployed | 5 formal governance policies (risk, architecture, exceptions, etc.) | 2 lightweight policies (project approval, vendor oversight) |

| Supporting Mechanisms | Templates, dashboards, workflows, architecture review protocols | One-page intake forms, checklists, basic documentation |

| Tooling Used | ServiceNow, Power BI, SharePoint, Jira | Email, shared folders, Confluence |

| Capability Building Approach | Role-based training, onboarding, KPI integration, governance champions | Informal modeling, meeting highlights, business-led reinforcement |

| KPIs / Metrics Tracked | Formal governance KPIs and dashboards | Informal tracking of outcomes and engagement |

| Cultural Reinforcement | Governance tied to leadership behaviors and organizational KPIs | Framed as shared discipline and decision support |

| Results | Unified intake, 63% reduction in ungoverned initiatives, cross-regional alignment | Reduced vendor risk, fewer project restarts, normalized governance language |

Key Takeaway:

Governance doesn’t scale by volume—it scales by fit. Whether it’s MetroLinea’s enterprise-grade program or ClearForge’s embedded simplicity, successful operationalization begins with context—and succeeds through commitment.

Why Governance Implementation Fails (and How to Avoid It)

Every governance framework looks good in a PowerPoint deck. Every committee charter sounds reasonable in theory. But in practice, governance doesn’t fail because it’s misunderstood. It fails because it’s misapplied, misaligned, or simply allowed to fade.

Understanding why governance fails isn’t just an academic exercise—it’s a prerequisite for sustaining it. Below are the most common failure points, drawn from real-world experience, and how organizations can sidestep them.

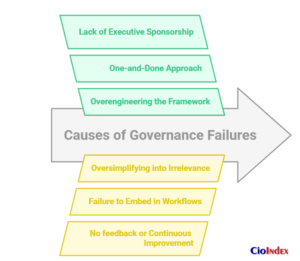

Leadership Signals Support—Then Disappears

Governance needs more than a C-suite signature. It needs C-suite presence. When executive sponsors introduce governance and then vanish, it sends a clear message: this is optional. This is theater. This is “an IT thing.”

In successful implementations, leaders do more than endorse governance—they model it:

- They participate in reviews.

- They demand transparency in portfolios.

- They challenge misaligned investments.

- They support unpopular but necessary decisions.

Without that visible reinforcement, governance becomes a checkbox. And checkboxes don’t change behavior.

Over-Engineering the Framework

Governance that tries to do everything ends up doing nothing. Organizations sometimes take frameworks like COBIT or ITIL and implement them wholesale—policies, structures, roles, workflows—without tailoring for context or capability.

The result? Complexity masquerading as maturity.

Governance should be fit for purpose, not built for audit. If teams can’t explain how a governance process works without referencing a diagram, it’s probably too complicated to survive contact with reality.

Oversimplifying It Into Irrelevance

On the flip side, governance can also be too loose. Some organizations are so afraid of bureaucracy that they implement governance in name only—light principles, vague roles, and no real escalation authority.

This breeds a different kind of risk: ambiguity. Decisions float. Accountability blurs. And when something fails, no one quite knows who said “yes.”

Governance isn’t red tape. But it is tape. It binds strategy to execution, decisions to accountability, and actions to outcomes.

Not Embedding Governance Into the Flow of Work

Governance doesn’t work when it’s external to real workflows. If your project approvals happen in one tool and your governance gates in another, you’ve just added friction. And friction is the enemy of compliance.

Successful organizations embed governance where the work happens:

- Intake in Jira or ServiceNow

- Architecture reviews linked to planning cycles

- Dashboards integrated into performance reviews

Governance shouldn’t require a second system. It should feel like part of the system people already trust.

One-and-Done Mentality

Governance isn’t a project—it’s a capability. But many organizations treat it like a launch event. They design it, roll it out, send the email, and then move on.

What happens next is predictable: the committee stops meeting. The metrics stop updating. The policies become outdated. And the next major project bypasses governance entirely—because no one remembered it was there.

Governance needs a sustainment plan:

- Scheduled reviews

- Maturity assessments

- Ownership transitions

- Feedback loops

Otherwise, it becomes a memory rather than a mechanism.

No Feedback, No Improvement

Governance that never changes becomes the very thing people fear—bureaucracy for its own sake. If there’s no way to question the process, raise concerns, or adapt policy to new conditions, governance turns from enabler to obstacle.

The most mature organizations build governance that evolves:

- Quarterly retrospectives

- Open channels for feedback

- Lightweight policy review boards

- Cultural permission to challenge the system constructively

Governance isn’t fragile. But it is perishable. It must be maintained, adapted, and revalidated.

Most governance initiatives fail not for lack of structure, but for lack of fit, ownership, and feedback. The visual below summarizes the most common causes of failure—each one preventable.

The Root Cause Isn’t Governance. It’s Neglect.

Governance doesn’t fail because the model was wrong. It fails because the model wasn’t lived. Because it didn’t evolve. Because people stopped treating it as something worth protecting.

The good news? These failures are predictable. Which means they’re avoidable.

When governance is:

- Sponsored from the top

- Right-sized to the organization

- Embedded in real workflows

- Owned across levels

- Reviewed and improved regularly

…it becomes what it was always meant to be: the discipline that keeps strategy and execution on speaking terms.

In Conclusion

Governance doesn’t live in frameworks. It lives in behavior.

You can have the clearest principles, the most elegant charters, and a library of policies. But if governance isn’t embedded in how decisions are made, how priorities are set, how exceptions are handled—it isn’t governance. It’s optics.

Implementation is where the discipline becomes real.

This article explored what it takes to move from strategy to structure, and from structure to execution. We examined how two very different organizations—MetroLinea and ClearForge—translated governance into action, each with tools, cadence, and policies that reflected their scale and complexity. One didn’t need dashboards. The other couldn’t operate without them. But both succeeded for the same reason: they treated governance not as an overlay, but as an operating model.

We also looked at why governance efforts fail—and the list wasn’t surprising:

- Executive disengagement

- Process complexity

- Cultural resistance

- A failure to adapt

What matters isn’t avoiding these pitfalls entirely. What matters is designing governance to survive them—to flex under pressure, to learn from feedback, and to scale with ambition.

Governance is not a solution. It is a capability. And like any capability, its strength is measured not by how it starts, but by how it evolves.

If you want governance that lasts, don’t start with frameworks. Start with decisions. Start with outcomes. Start with the organizational moments where clarity is missing, risk is rising, and alignment is off course.

Because that’s where governance matters most—and where it either works, or it doesn’t.

To explore how to tailor your governance operating model, benchmark maturity, or integrate compliance and innovation, see our full IT Governance resource collection